Grand National fences & course

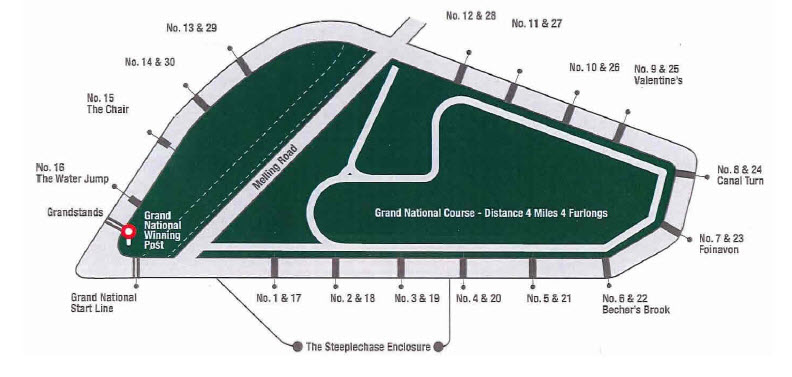

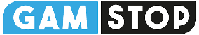

Last Updated 13 Feb 2025 | By The GrandNational.org.uk StaffThe Grand National fences are the ultimate test of horse and jockey. The iconic race comprises two complete circuits of a unique 2¼ mile (3,600 metres) course at Aintree. The runners and riders will face 30 of the most testing fences in the world of jumps during their 2025 Grand National runs. Entered horses known to be good jumpers will likely feature in the list of Grand National favourites.

Aintree’s unique course contributes to the mystique surrounding the big event. The fence-building programme starts roughly three weeks before the Grand National meeting, with around 150 tonnes of spruce branches sourced and transported from forests in the Lake District. Each fence is made of a wooden frame and shielded with distinctive green spruce.

Becher’s Brook, the sixth fence on the first circuit, is named after Captain Martin Becher. The jockey led in the first-ever Grand National in 1839 but became unseated from his mount, Conrad, and fell into the ditch. “Water tastes disgusting without the benefits of whisky,” he humorously reflected, and the obstacle has borne his name since that day.

The first running of the Grand National at Aintree in 1839 featured a solid brick wall as one of the obstacles. Luckily for both the Jockeys and their mounts, this fence was wisely removed after five years.

Prior to the 2013 contest, some fences were re-designed for safety reasons and to aid animal welfare. While all 16 fences appear similar to before the changes, four of them were changed. The 3rd and 11th fences now have natural birch as their cores, while the 13th and 14th now have plastic birch, replacing the traditional rigid timber frames.

How many fences are in the Grand National?

There are 16 fences on the Grand National course, 14 of which are jumped twice along the four mile, two and half furlong marathon distance. The Chair and the Water Jump are the two Grand National fences that are only jumped once.

The early history of Grand National fences

The Grand National was originally designed as a cross-country steeplechase when it was first officially run in 1839. The runners started on the edge of the racecourse, racing out over open countryside towards the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. The gates, hedges and ditches that they met along the way were flagged. These provided them with the earliest incarnation of today’s Grand National fences to be jumped along the way. Posts and rails erected at the two points where the runners jumped a brook.

The runners returned by running along the edge of the canal before re-entering the course at the opposite end. The runners then ran the length of the racecourse before the second circuit and finish at the stands. The majority of the race, therefore, took place not on the actual Aintree Racecourse but instead in the adjoining countryside. That countryside was incorporated into the modern course but commentators still often refer to it as “the country”. This confuses millions of once-a-year racing viewers.

Nowadays, around 150 tonnes of spruce branches from the Lake District, are used to dress the Grand National fences. Each fence used to be made from a wooden frame and covered with the distinctive green spruce. However, a radical change for the 2013 renewal saw that frame replaced by a softer material known as “plastic birch”.

Each of the 16 Grand National fences are jumped twice, with the exception of The Chair and the Water Jump. They are jumped on the first circuit only.

The Start

There is a hazard to overcome even before the race starts. The build-up, parade and re-girthing prior to the off lasts for around 25 minutes. This is over double the time it takes for any other race.

With 40 starters, riders naturally want a good sight of the first fence. After the long build-up, their nerves are stretched to breaking point. This means the stewards’ pre-race warning to go steady is often totally ignored.

The Grand National fences

1 & 17: Thorn fence, 4ft 6in high, 2ft 9in wide – The first often claims many victims as horses tend to travel to it far too keenly. As described above, the drop on the landing side was reduced in 2011.

2 & 18: Almost the same height as the first but much wider at 3ft 6in. Prior to 1888, the first two fences were located halfway between the first to second and second to third jumps. The fence became known as The Fan after a mare refused at the obstacle three years in succession. But it lost that name when the fences were relocated.

3 & 19 Westhead: This is the first big test with a 6ft ditch on the approach guarding a 4ft 10in high fence.

4 & 20: Plain fence, 4ft 10in high and 3ft wide. In 2011, the 20th became the first fence in Grand National history to be bypassed. It followed an equine fatality on the first circuit. In 2012, it was reduced in height by 2 inches to 4 foot 10 inches (1.47 metres). It was regarded as the hardest fence on the course to jump, along with Becher’s Brook. Its landing area was smoothed out ahead of the 2013 race.

5 & 21: Spruce dressed fence, 5ft high and 3ft 6in wide. Its landing side was also levelled in 2013. It was bypassed on the final lap for the first time in 2012. Medics needed to treat a jockey who fell from his mount on the first lap and had broken a leg.

Becher’s Brook

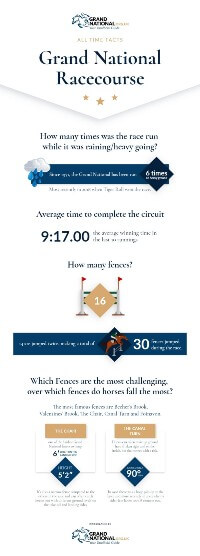

6 & 22 Becher’s Brook: Although the fence looks innocuous from the take-off side, the steep drop on the landing side, together with a left-hand turn on landing, combine to make this the most thrilling and famous fence in the horse racing world. The fence actually measures well over 6 ft on the landing side. A drop of between 5 and 10 in from takeoff lies on the other side. Horses are not expecting the ground the disappear under them on landing. Riders need to sit back and use their body weight to act as ballast to keep the horses stable.

As described above, there have been a number of alterations to make it fairer and safer for horse and rider. The whole field managed to clear the obstacle on the first circuit last year.

Graphic by Elizabeth Goldsmith at Equine Link.

Becher’s Brook earned its name as one of the most famous Grand National fences when a top jockey, Captain Martin Becher, took shelter in the brook after being unseated. “Water tastes disgusting without the benefits of whisky” he reflected.

7 & 23 Foinavon: Basically an ‘ordinary’ fence (4ft 6in high and 3ft wide) that was made famous in 1967 when Foinavon was the only horse to scramble over it at the first time of asking, following a mass pile-up. The jump is the smallest on the course. Though, coming straight after the biggest drop, it can catch horses and riders out.

The Canal Turn

8 & 24 Canal Turn: Made of hawthorn stakes covered in Norway spruce, it gets its name from the fact that there is a canal in front of the horses when they land. To avoid it, they must turn a full 90 degrees when they touch down.

The race can be won or lost here. A diagonal leap, taking the fence at a scary angle reduces the turn-on landing. With 30 or more horses often standing at this point, not every rider has the option to take this daring passage. Before the First World War, it was not uncommon for loose horses to continue straight after the jump. They’d end up in the Leeds and Liverpool Canal itself. There was once a ditch before the fence but this was filled in after a mêlée in the 1928 race.

Valentine’s Brook

9 & 25 Valentine’s Brook: The third of four famous fences to be jumped in succession. It is 5ft high and 3ft 3in wide with a brook on the landing side that’s about 5ft 6in wide. The fence was originally known as the Second Brook. But it was renamed after a horse named Valentine was reputed to have jumped the fence hind legs first in 1840.

10 & 26: Thorn fence, 5ft high and 3ft wide that leads the runners alongside the canal towards two ditches.

11 & 27 Booth: The main problem with this fence, which is 5ft high and 3ft wide, is the 6ft wide ditch on the take-off side.

12 & 28: Same size as the two previous fences, but with a 5ft 6in ditch on the landing side, which can catch runners out.

The runners then cross the Melling Road near to the Anchor Bridge. It’s a popular vantage point since the earliest days of the race. This also marks the point where the runners are said to be re-entering the “racecourse proper”. In the early days, it was thought there was an obstacle near this point known as the Table Jump. It may have resembled a bank like those seen at Punchestown in Ireland. In the 1840s the Melling Road was also flanked by hedges and the runners had to jump into the road and then back out.

13 & 29: Second-last fence on the final circuit, it is 4ft 7in high and 3ft wide. This is the other obstacle to have had its landing side smoothed out ahead of the 2013 renewal.

14 & 30: Almost the same height as the previous fence and it is rare for any horse to fall at the final fence in the Grand National.

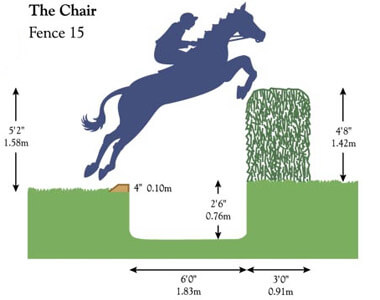

The Chair

15 The Chair: The final two jumps of the first circuit form the only pair negotiated just once. They couldn’t be more different. The Chair is both the tallest (5ft 2in) and broadest fence. It has a 6ft wide ditch on the take-off side.

Graphic by Elizabeth Goldsmith at Equine Link.

The landing side turf is actually raised six inches above the take-off ground. This has the opposite effect to the drop at Becher’s. After having stretched to get over the ditch, horses are surprised to find the ground coming up to meet them. This is spectacular when horses get it right and, for all the wrong reasons, when they don’t.

This fence is the site of the only human fatality in the National’s history. Joe Wynne sustained injuries in a fall in 1862. This brought about the ditch on the take-off side of the fence. The fence was the location where a distance judge sat in the earliest days of the race. On the second circuit, he would record the finishing order from his position. He would declare any horse that had not passed him before the previous runner passed the finishing post as “distanced”, a non-finisher. The practice ended in the 1850s but the monument where the chair stood is still there.

The fence was originally known as the Monument Jump but The Chair came into more regular use in the 1930s.

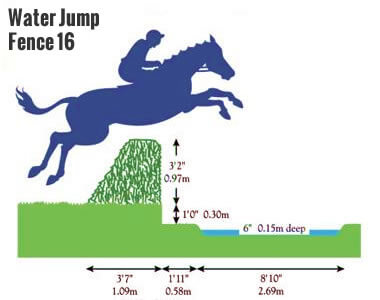

16 Water Jump: This 2ft 9in fence brings the first circuit to an end. The sight of the runners jumping it at speed presents a terrific spectacle in front of the grandstands. The fence was originally a stone wall in the very early Grand Nationals. On the final circuit, after the 30th fence, the remaining runners bear right, avoiding The Chair and Water Jump, to head onto a “run-in” to the finishing post.

Graphic by Elizabeth Goldsmith at Equine Link.

The Finish

The 474-yard long run in from the final fence to the finish is the longest in the country. It has an acute elbow halfway up it that further drains the stamina reserves of both horse and jockey.

For numerous riders, this elongated run-in has proved mental and physical agony. The winning post seems to be retreating with every weary stride.

Don’t count your money until the post is reached as with the rest of the Grand National course. The run-in can, and usually does, change fortunes. The likes of Devon Loch, Crisp and Sunnyhillboy have all famously had defeat snatched in heat breaking fashion.

Safety changes to the Grand National fences

Safety reviews after the 2011 and 2012 races, led to a number of changes to the course. This included some reductions in Grand National fences or the drop after fences, plus the levelling of landing zones.

Since 2013, the start of the race is now 90 yards closer to the first fence. This reduced the race to four miles and three-and-a-half furlongs, from four-and-a-half miles. Measures were also introduced to stop horses getting caught up in the starting tape.

In particular, the start now includes the ‘no-go’ zone. This is defined by a line on the track extended from 15 to 30 yards from the starting tape. The starter’s rostrum has been moved to a position between the starting tape and the ‘no-go’ zone. This reduces the potential for horses to go through the starting tape prematurely.

The tapes themselves are also more user-friendly, with increased visibility. While there is now a specific briefing between the starters’ team and the jockeys on Grand National day.

The changes to the start are aimed at slowing the speed the first fence is approached at. While moving the start further away from the crowd reduces noise that can distract the horses.

The makeup of all of the Grand National fences changed significantly in 2013. The new fences are still covered in spruce, but wooden posts have been replaced by “plastic birch”. On top of that birch, there are fourteen to sixteen inches of spruce that the horses can knock off. The outward appearance of the Grand National fences remains the same.

Other measures included £100,000 being invested in irrigation to produce the safest jumping ground possible. This includes a new bypass and pen around fence four to catch riderless horses.

Course Walking

No visit to Aintree would be complete without taking the opportunity to see some of these famous fences close up. The whole course can actually be walked on the morning of the race (subject to ground conditions and security requirements). Walkers should leave an hour to do a circuit, which must be completed one hour prior to the first race. Maps, guiding racegoers to the start point, are located around the racecourse.

Grand National fences FAQ

Find answers to some common questions relating to the Grand National fences in the section below.

What are the fences called in the Grand National?

The majority of the Grand National fences have gained names over time. Some, like the Water Jump and the Canal Turn, relate to the type of fence or where the fence is located on the Aintree course. Others, including Foinavon and Becher’s Brook, are named after famous horses that ran in previous Grand Nationals.

Which fences are only jumped once in the Grand National?

The Chair and the Water Jump are the two Grand National fences that are only jumped once.

Are the fences lower in the Grand National?

Grand National fences vary in height, with the majority being around 5ft high. The Chair is the highest fence, at 5 foot 2 inches, while the Water Jump is by far the lowest at just 2 foot 6 inches.

At which fence do most horses fall in the Grand National?

Horses will fall at every fence during the Grand National. Two of the most challenging fences are The Chair, due to its height, and Becher’s Brook, due to its steep landing.

Our Content

*We hope you enjoyed the selection bookies we recommended! Just to be clear, grandnational.org.uk may collect a share of sales or other compensation from the links on this page.

You might also like…

[wp-review id=”64″]